Vir Andres Hera

Born in 1990

Lives and works in Savoy

پیرامیدال Piramidal, 2016

View of the exhibition QALQALAH: more than one language, Kunsthalle, Mulhouse, 2021

© Vir Andres Hera

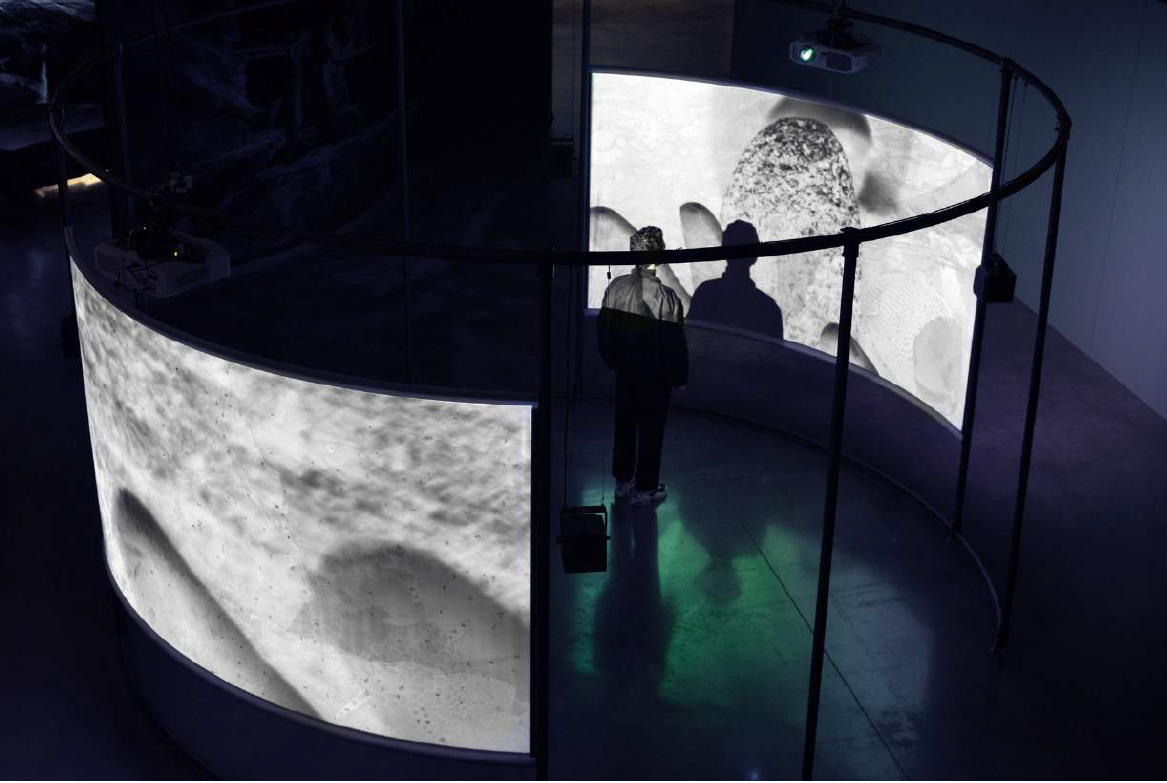

Misurgia Sisitlallan, 2019-2020

View of the installation created for the exhibition Panorama 22 - Les Sentinelles, Le Fresnoy - Studio national des arts contemporains, Tourcoing, 2020

© Vir Andres Hera

Le Romanz de Fanuel, 2017

20’, 16mm cinemascope

© Vir Andres Hera

“Nothing is lost, nothing is created, everything changes.”

This quote by Lavoisier wouldn’t be out of place above the door to Vir Andres Hera’s studio. Indeed, his entire approach consists in going against the idea of an expiration of culture. So there he is, phonetically transcribing a 17th-century Mexican nun’s poems into Arabic. There is no world in which he’ll let Sister Juana Inés de la Cruz be confined to an ancient, Western and elitist culture. There he is again in the botanical gardens, camera pointed at an old herbarium so that he may, through the use of montage, breathe new life into the flowers collected during the royal expedition to America. And there again, following the backward walk of a Tlapaneco native woman, aware that she is speaking a dead language in a living and modern body. But is she really walking backwards? Pushing aside positivistic art theories, Vir Andres Hera continually asks us the following question: what is going backwards and what is moving forwards? What if history was just a gigantic palimpsest written by the same man? This is what he seems to say in the book he published under the title Pieter Van Gent, the mysterious and supposedly immortal author of a 777-page palimpsest, who lives through the history of Mexico from Spanish colonisation to the late 20th century. And the land, its architecture and its toponymy seem to be the only stable references in this vast journey through time.

It is precisely because the artist is fascinated by diversity and because, like Victor Segalen’s exoticist, he “experiences the flavour of the diverse”, that he can lose himself in it and bring us along with him — but only to better fish us out of it. In fact, faced with the dizzyingly abundant production of cultural goods, Vir Andres Hera always seeks to draw our attention back to what remains. This obsession with permanence has for instance led him to the Basque Country, to the sites that inspired Pieter van der Meulen’s painting The Exchange of the Princesses of Spain and France on the River Bidasoa, in order to observe what is left of this exchange of women in the old port. His approach is by no means archaeological: it does not exhume the past but, rather, prolongs its spells, giving a new lease of life to what humankind once created. One often says that translating is betraying: on the contrary, Vir Andres Hera’s artistic approach is consumed with faithfulness.

Vir Andres Hera, Artist of the Casa de Velázquez — Académie de France in Madrid, text by Amine Damerdji, 2016.

Translated by Lucy Pons, 2024